Plato's Regimes and the Ideal Form of Government

A deep dive into the five different regimes established in Book VIII of Plato's Republic.

Reading time: 15 mins.

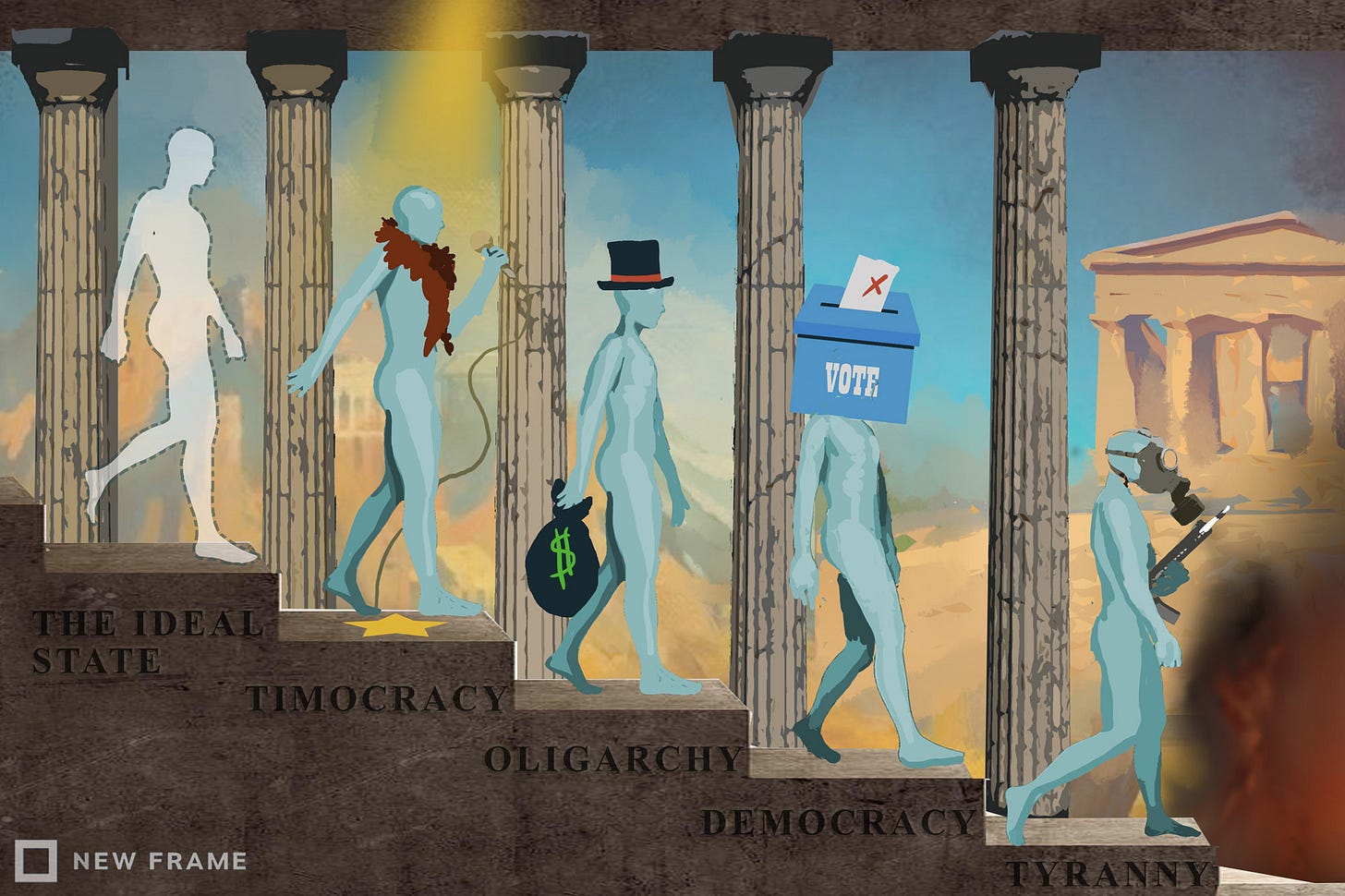

Around 375 BCE, Plato published The Republic, which served as a blueprint of interpretation for other philosophers such as Aristotle from before the Common Era and also philosophers such as John Locke from the Modern Era. In Book VIII of The Republic, Plato establishes that there are five kinds of government. These are timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, tyranny and aristocracy. Plato states that of these five principal forms of regime, four are defective, or less than perfect, while one of them is the preferred form, deemed by Plato as the ideal form of government.

The first of these forms of government discussed in The Republic is timocracy, or the rule for the sake of honor. This regime is motivated by ambition and love for honor and, according to Plato, it is the regime that naturally follows aristocracy. Specifically, he states, “Clearly, the new state, being in mean between oligarchy and the perfect State, will partly follow one and partly the other” (Plato 2). This statement by Plato, during his conversation with Glaucon, implies that timocracy is sort of a mixture between oligarchic tendencies and tendencies from aristocracy—the perfect state. This is formed after the “philosopher king” is preceded by someone who is not fit to rule on the basis of reason and understanding and gives rise to oligarchic tendencies such as the glorification of war and acquisition. Money and status begin to characterize the individual and, as the timocratic ruler begins to grow into his role as leader, his ability to rationalize is greatly severed next to passion and appetite. Finally, as Glaucon eloquently put it, “Undoubtedly … the form of government, which you describe, is a mixture of good and evil,” to which Plato replied, “Why there is a mixture … but one thing … is predominantly seen, --the spirit of contention and ambition … due to the prevalence of the passionate or spirited element,” when referring to the way the timocratic man pursues his actions (Plato 3).

The next form of government is none other than oligarchy, or the rule of the few. This regime deals with a small group of people having the majority of control within the state. Plato defines oligarchy as “a government resting on a valuation of property, in which the rich have power and the poor man is deprived of it” (Plato 4). The sentiment here is that an oligarchy is not in reality one state but two, divided between the rich and the poor. Nearly all who are not in a position of power are poor. This type of regime, according to Plato, follows after timocracy dives too deep within avarice and passion, so deep that citizens become haunted by it. He states, “the accumulation of gold in the treasury of private individuals is the ruin of timocracy.” Moreover, “one, seeing another grow rich, seeks to rival him, and thus the great mass of the citizens become lovers of money” (Plato 5). This creates the belief within the state that rich men and riches are what is honored, and that virtues are dishonored.

The third regime discussed in The Republic is democracy, or the majority rule of the people. In this form of government, the majority of the population are in control of the state and their decisions are intended to benefit the many and not the few. According to Plato, this occurs when the poor rise up against the rich in an oligarchic state and conquer them, executing some while ridding the others of power. He states, “democracy comes into being after the poor have conquered their opponents, slaughtering some and banishing some, while to the remainder they give an equal share of power.” This is a regime of freedom, where the individual can “order for himself his own life as he pleases” (Plato 11). In this freedom prevails the “forgiving spirit of democracy,” where the sentiment within the regime is one that has little regard for anything, be that honor, wisdom, or duty, placing only importance on the great freedom that has been bestowed upon its state and citizens (Plato 12). In other words, law and order are sacrificed to liberty and equality.

The fourth and final defective regime in Plato’s The Republic is none other than tyranny, or the rule by a despot. A despot is someone who holds absolute power over the state and typically exercises that power in a cruel and oppressive way. Ironically, Socrates calls tyranny “the most beautiful of all” constitutions because of the simplicity and uniformity of it. This regime is formed when the democratic man has “drunk too deeply of the strong wine of freedom” (Plato 15). This stems from the unsatiable desires of the public in a democracy, concerning freedom. The citizens “chafe impatiently at the least touch of authority,” which in turn has them turn to the tyrannical man who claims he will restore these freedoms (Plato 16). The citizens, now in this tyrannical state, must obey the head of state’s every wish and desire, or be punished severely for it. They do not—initially—rise against this oppressive state because they are either too blind to see the truth or too scared to enforce it themselves. Eventually, tyranny acts as a sort of eye-opener for the citizens that were previously complaining about their freedoms in a democracy and their lack of riches in an oligarchy, leading them to eventually instate—if it wasn’t already in place previously—what can only be described by Plato as the “perfect state” (Plato 2).

As mentioned before, the previously discussed forms of government are all flawed in the eyes of Plato. These four “defective” forms are timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and finally tyranny. The transitions between all of these regimes, with the exception of tyranny, comes from an insatiable desire from either the minority or the majority that turns into a battle between the two in order to see which comes out on top.

New Frame. A visual representation of the transition between regimes.

The transition between timocracy to oligarchy is quite simple. First, the warriors who are enveloped in the idea of honor and ambition grow so attached to this belief that it naturally consumes them. For instance, take a man who was the commander of an army in a successful battle. In a timocratic regime, his accomplishments as commander will bring him great amounts of appreciation and glory from the citizens upon his arrival to the city. These appreciations turn into riches and feelings of lust and greed, which now the commander feels he deserves because of his great accomplishments in war. This is what directly causes the transition from timocracy to oligarchy, an unsatiable desire for glory and acquisitions that can never be fulfilled. Leading the timocratic state to become an oligarchic one, in which the rich prosper while the poor steadily become poorer and have less of a say in political matters.

The next transition that occurs is the transition between oligarchy and democracy. This initially occurs by the obvious fact that the majority of citizens are currently poor and have astronomically little say in what goes on within their state. This becomes a revolution of sorts in which the poor rise up against the rich, “slaughtering some and banishing some” as mentioned before (Plato 11). The natural problem with democracy is that, once the majority gets control over the state, they also become unsatisfied with yet another insatiable desire; freedom. This form of government also involves equality because of the divisiveness between the rich and the poor during an oligarchic state, but the main idea of a democracy in Plato’s The Republic is freedom. Citizens begin to propose “fairer” laws for the benefit of the majority, while undermining the minority. This lust for freedom transforms into somewhat of a sacrifice, in which the state sacrifices integrity, law, and order for the newly glorified ideals of equality, representation, and freedom. This is what makes the democratic state so dangerous; it appeals to ideals that everyone wants, but the disorder will most likely interfere with the principles of good government and virtue. This goes down to the basic fact that in a democracy, not every single citizen can be happy with the current state of affairs. This in turn marks the beginning of the end for democracy, when, as eloquently expressed by Plato, the democratic man has “drunk too deeply of the strong wine of freedom”—as briefly mentioned before (Plato 15). Causing the shift from a democratic regime to a tyrannical one.

The final transition between the four non-perfect states, according to Plato’s The Republic, is between democracy and tyranny. This occurs from the flaws that sacrificed law and order for freedom in a democratic state. The ones who feel that their freedoms have become threated by any display of order or restrictions, turn to a single entity who will restore these freedoms to them—the tyrannical man. In the beginning, the tyrannical man might not even seem as a bad, power-driven person—in fact—his current duty is to reestablish the freedoms his followers claim they have lost. He does this by challenging the powers that are in control of the democracy (the majority) and establishing a permanent seat of power for only himself in the state. Once in this state of power, the tyrannical man reveals his true nature and the betrayed followers finally acknowledge the grand mistake they have made. Most of the oppressed citizens in a tyrannical government agree that something must be done to correct this mishap, but by giving a single individual so much power it becomes nearly impossible to challenge his authority without immediate consequences. The few who do not see this still blindly believe that the tyrannical man will restore their freedoms, and that such measures of oppression are necessary for that to happen. The reality is that most are too scared to speak up against him because it would mean that they will be punished, often publicly, in a severe manner. Eventually these people realize that they took all of their previous liberties for granted and decide to establish—if not reestablish—a perfect state; an aristocratic regime.

The ideal regime expressed in Plato’s The Republic is aristocracy, or the rule by a philosopher king. As stated previously, this is the type of government that Plato idealizes. An aristocracy is composed of three caste-like parts: the guardians (ruling class), the auxiliaries, and the majority. The guardians are made up of philosopher kings, who are grounded on the basis of knowledge and wisdom to make decisions; they are considered to have souls of gold in The Republic. The auxiliaries are composed of soldiers who will enforce the wise policies the ruling class puts out; they have souls of silver. Finally, the majority is made up of citizens who do not fall within the previously mentioned castes which are allowed to own property and produce goods for the benefit of all; they have souls of bronze or iron.

Raphael’s School of Athens, depicting Plato and Aristotle in the center.

Plato argues that aristocracy is the best form of government for many reasons, but primarily because it is a regime centered on the basis of reason and wisdom. In an aristocracy, the rule of the few is for the benefit of the many; no guardian has any unsatiable desire and instead, are dedicated to their work which is to make laws and regulations that are reasonable. Unlike the flawed regimes, an aristocracy has no insane desires that could never be achieved by the ruling class. The next caste, the soldiers, also have an important purpose in government; they are in charge of enforcing the rules laid out by the guardians and of maintaining the order and peace within the city. Lastly, the majority is allowed to have property of their own and are advised to produce goods for themselves, the soldiers, and the guardians. This is the best state because it is one that is well-balanced and has a respectable social hierarchy, where everyone has a purpose to maintain and improve the state and thus, no one feels left out.

As one can easily see, all forms of government in Plato’s The Republic have some sort of downfall. The timocratic man is too obsessed with honor and passion, the oligarchical man is too obsessed with greed and riches, the democratic man is too obsessed with freedom and equality, and finally, the aristocratic man is perfect until someone unfit to rule takes charge, causing the cycle to repeat itself once again. It is true that aristocracy might be the best of these regimes—according to Plato—but even the nature of the most perfect regime is destined to fail at some time or another due to the conflicting nature of humans.

References

Plato. "Plato, Republic, Book 8". Perseus.Tufts.Edu, 2020, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0168%3Abook%3D8. Accessed 15 Jan 2022.

Course Hero. “The Republic By Plato | In-Depth Summary & Analysis.” YouTube. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P4fydrydX5o. Accessed 18 Jan 2022.